Where were you during the Great MOOC Panic of 2012?

I was in Massachusetts, taking a class in educational technology, when the Boston Globe announced the launch of EdX. My instructor put aside his syllabus that day, and my classmates and I spent the rest of our semester monitoring the developing story and punditry, and working out our own thoughts on the likely future of higher education. The promise of the new model didn’t escape us; free education makes its own case when you’re putting down cash for an advanced degree.

That said, the reaction to EdX that week included no small dose of near-panic. The thought of a college class that could enroll students a half-million at a time, for no charge, backed by educational giants such as Stanford and Harvard, led to animated discussion about what role, if any, traditional schools could carve for themselves in the new landscape. Trade publications reported any data they could find about the developing success, or failure, of the new classes as soon as it became available. American higher education baited its breath as it sized up the new giant.

One year later, the pace of the MOOC discussion seems to have subsided. News about the model is less frequent, and most colleges that existed before EdX have not closed their gates. The pause in the engagement allows a chance to consider MOOCs’ rise over the past year, but also gives rise to a question of its own; what happened to the Great MOOC Panic that, a year ago, was gripping administrators and commentators? Below are some thoughts about where all the discussion has gone:

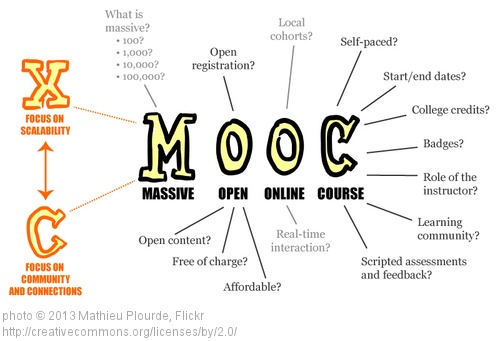

1) MOOCs have proven their worth --and their limitations. It’s been about a year since Harvard and MIT launched Edx. In that time, the strengths and weaknesses of the model have largely shaken out. Certainly, the program has demonstrated some impressive capability, especially in terms of networking and access. EdX bundles classes from twenty-nine colleges in twelve countries. These maintain an enrollment of up to 150,000 students in a class, with an estimated total enrollment of about one million.

That said, this impressive community has fallen short in some important aspects. Student retention, has been especially low. In early classes, only ten percent of enrollees completed their course. Credentialing MOOC-based learning has raised issues. And many academic subjects have proven to be difficult fits for pure online delivery. These particular problems, and others, speak to a strong continuing role of relatively local institutions prepared to assess and teach manageable numbers of selected students, in a more-or-less conventional academic structure.

2) Schools have set their course, and found their way. Since EdX launched, many institutions have aggressively managed their strategy for keeping, or even improving, their relevance in the face of the MOOC emergence. These prescients have charted a navigable course for institutions. Larger, more prestigious schools have followed MIT and Harvard in becoming contributors, teaching the classes that EdX offers on a massively open basis.

Other programs have aligned themselves as consumers to supplement their own programming. Rather than merely compete with existing colleges, EdX has aggressively sought to partner with them in mass blended-learning arrangements. To date it has opened programs with the Massachusetts community college system, California State University, a consortium of major Chinese universities, and the French Ministry of Higher Education to launch blended classes and portals.

3) Other actors are weighing in, and saying “not yet.” Institutions, and MOOC’s, don’t exist in a vacuum. Their success depends in part on their own efforts, but also on their relationships with a number of other actors. Recently, the philosophy department at San Jose State University refused to teach a blended EdX course, citing the apparent dismantling of locally-controlled public education.

In countries where government plays a more direct hand in national economy management, schools and their roles are held firmly --and very directly-- in a balance with each other and with national interests by public regulation. The Turkish government sponsors its own free massively open university, and intensively oversees it and other public and private schools through direct oversight of enrollment quotas, entrance examinations, academic requirements for completion of degrees, and other administrative matters.

MOOCs have certainly demonstrated a capacity to play a significant role in higher education, and their potential impact should not be overstated. They have been especially powerful motivation for institutions to update their conventional perspectives on sound, relevant education. That said, an apocalyptic collision with the status quo seems to have been averted, especially since they seem to be relying on traditional colleges as a customer base. The role that MOOCs play in higher education is certainly worth watching, both for the opportunity and risk that it presents. But their growth, internationally and in America, will likely supplement rather than fundamentally threaten existing colleges for the immediate future.

Brendan O’Brine has worked in higher education since 2006. He holds a law degree from the University of California and recently completed his Master of Education at Northeastern University.