Unlike most of his peers, my son (it’s Carrie talking here) applied to just two higher ed institutions. He got into both. Accepted both. Put down a deposit on both. Will attend just one. And so, he’s part of the admissions problem.

Our colleague (and contributor to today’s post) Jon Boeckenstedt, retiring vice provost of enrollment management at Oregon State University, explains it like this: A lot of people think yield is like planting saplings in greenhouses, where your success is highly dependent on things you control, like spacing, soil quality, temperature, water, etc. In fact, yield is more like scattering seeds, where you are hopeful, and you have some ideas of success based on prior years, but in reality, you're at the mercy of factors you have zero control over.

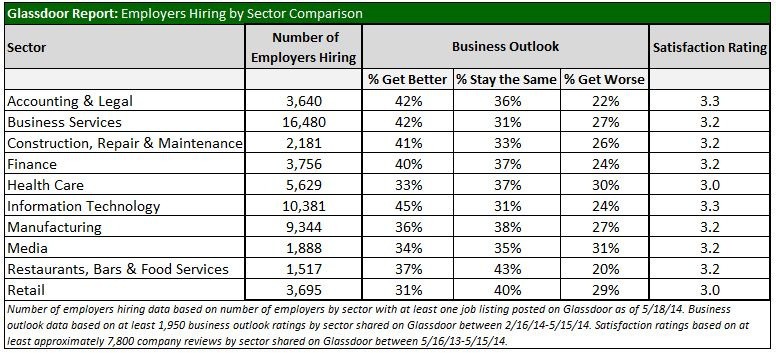

As an example: Last year, UCLA received 146,276 applications. About 13,114 students or 9% were admitted. For comparison, just 4 years earlier, in 2020, the university had an acceptance rate of 18%. And a decade+ ago in 2010, it was 23%. Go back further to 2000, it was 29%. And wait for it, in 1990, it was just above 40%. A lot has changed in a 30+ years.

| Year |

UCLA Acceptance Rate |

| 1990 | 40+% |

| 2000 | 29% |

| 2010 | 23% |

| 2020 | 18% |

| 2024 | 9% |

UCLA is not unique in this way.

Meet Intead!

- Find us at NACUBO in DC in July, and NACAC in Columbus in September. Be in touch to share a cup of coffee in person.

Bookmark this: Intead’s Resource Center

Access 800+ articles, slides decks, reports with relevant content on any topic important to enrollment management and student recruiting. Check it out.

Applications have skyrocketed for most institutions. For top-tier universities, this surge makes them even more selective (or rejective) — great for prestige and ranking supposedly, tough for admissions teams and applicants alike. For the majority of institutions, however, the steep rise in applications is just that, a steep rise in applications. Yield is on a different trajectory, and it’s driven by a simple concept: Algebra.

The rise in applications has dramatically outpaced the increase in college-bound students, and of course, a student can only enroll in one institution, whether they are admitted to two or twenty. This then leads to a big increase in the volume of ibuprofen intake by admissions teams, as predicting the behavior of students is getting harder all the time. While institution leaders continue to demand enrollment results.

Thank goodness for the consistent ibuprofen supply.

We can point to the Common App as the bane of the admissions process. But that’s not really fair. Its advent brought more students into the system, increasing access overall. So, there’s the good. And not every university seeing the surge uses the Common App, and the University of California system is among those that do not.

The real drivers of the application tsunami: access, competition, and coaching from influencers like school counselors and advisors. There are pros and cons to this situation. Ironically, the unpredictable nature of admissions decisions causes stress, which causes students to hedge their bets and apply to more colleges, which makes the admissions process less predictable.

For context:

- In 2000, the typical applicant applied to three to five institutions.

- Today, the average student applies to eight to 12+, simply because they can.

- In 1998, when Common App went digital, ~250,000 applications were submitted through it.

- In 2024, that number hit 7.3 million – a 2,820% increase. (Yes, they have many more institutions as clients today, but still!)

Read on…

Read More